Being scrolled over: a rock check

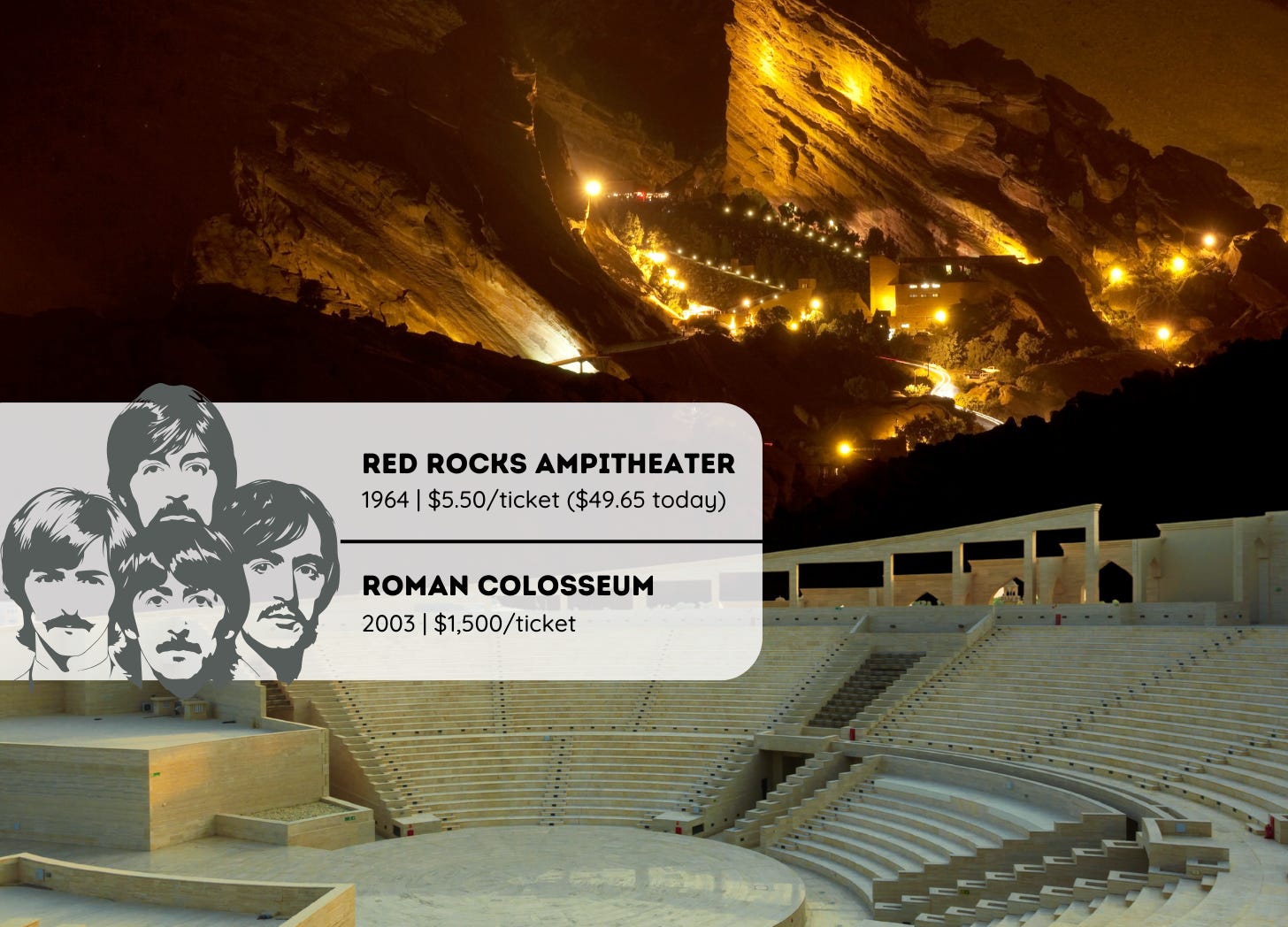

Once a week, someone stands in front of 9,525 people. Next to a 300-foot rock that rose from the ocean floor. And this is how that rock checks them.

Friends-

I never used to pay much attention to rocks.

When I’m up at 7,000 feet elevations, there seems to be way too many. But when I hold one rock in my hand, they feel unnecessarily singular.

One American rock did make me legitimately afraid, though.

This one:

The way this rock slants down towards the stage, makes you feel like you’re climbing down into an underworld.

Going down from up high always gives me a strange feeling in my lower torso. I could deal with going up. But going down to something—not so much.

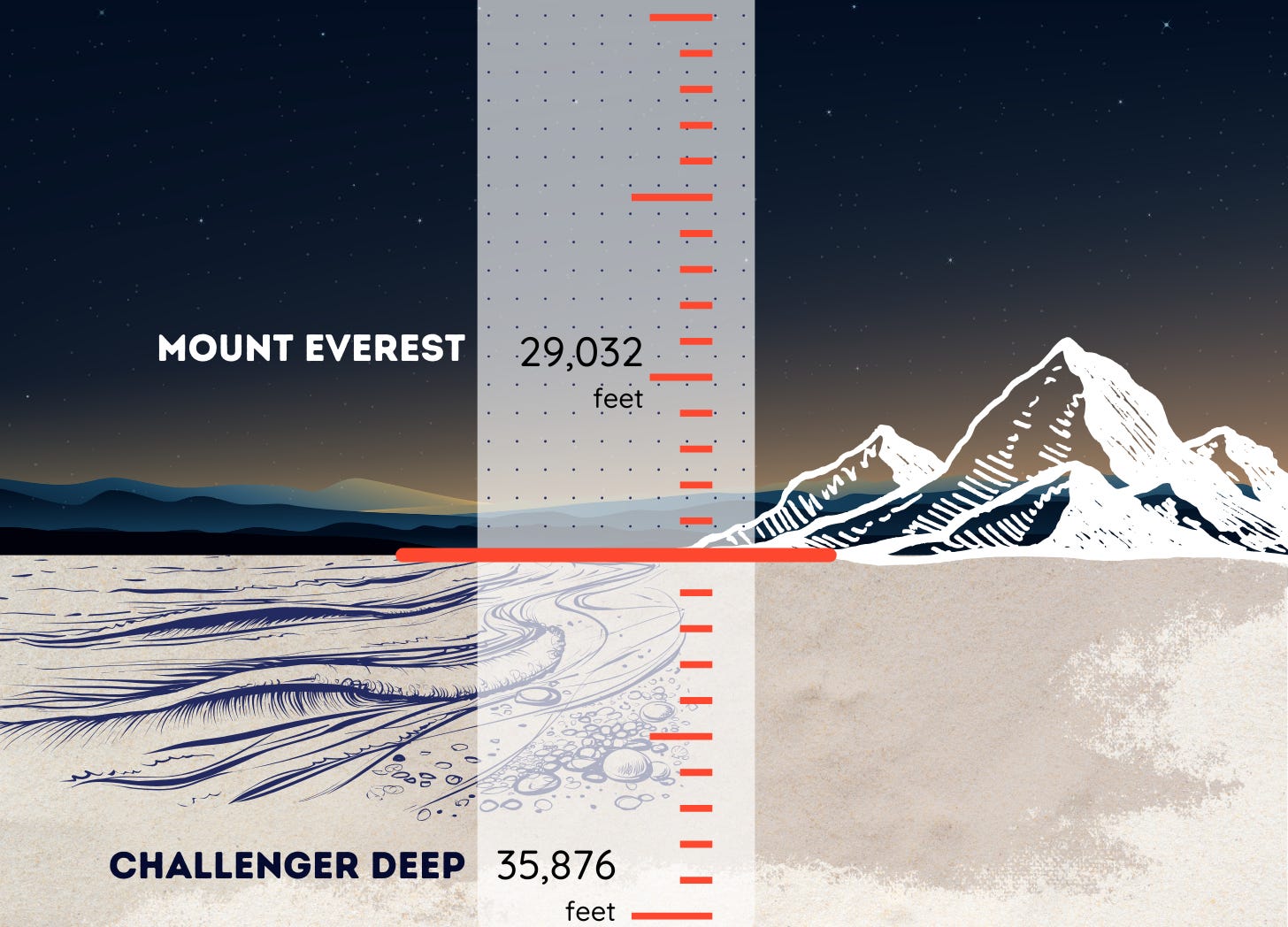

I know climbers and divers talk about this all the time. But when you go up an elevation, it’s hard to breathe. Not because you’ve eaten one too many tacos at lunch. But because there’s just not as much oxygen. An Everest climber I chatted with recently talked about the same problem.

Same thing when you go down below sea-level, your ears feel like they’re about to implode.

This time from pressure.

My first time scuba-diving, I knew this in theory. But boy was I schooled. They weren’t joking.

The dive down

Diving and climbing are both very romanticized. No, “glorified” is a better word. All we see are the nice pictures. The sunbathed boats. And healthy pink faces.

No one ever talked about the shock from the icy water when you jump out of the boat. Along the equatorial tropics where I grew up, you’d think the water would be warm. But it might as well be Iceland. Even after being covered head to toe like a confused newborn seal.

I’m thinking if a newborn seal ever do see a human in a wet suit, though, they’d go:

“What the hell … is that!?”

Regardless—in these circumstances, I could always hear the pounding of my heart.

My friends talk about fear of sharks. For some reason, for me it’s always been fear of drowning. I must’ve been very scared of the water at one point in my life. But I guess growing up in a country that has over 17,500 islands does things to your imagination.

Underwater, everything slows.

Kicks aren’t abrupt. They slide. Hand-waves aren’t jerky. They are limp.

The group of us was supposed to stay together. But you just get lost in the beauty. A purple fish zoomed three inches in front of me. And I just can’t help but follow it. Even to dark corners.

Whether it’s minutes or seconds long, who knows.

The next thing, I turned to look, and I was a good hundred feet away from the pack. Which doesn’t sound like far. But when everything around you is deep blue, it does.

Back then—there was no audio. Nothing to call out to our fellow divers. For a second I wanted to scream for help. But a moment of sense saved me. If I take my lips off that oxygen, it’s over.

This whole time, they are just checking out a group of corals. Completely unaware I had split. And I just felt a sudden chill. There’s the very real feeling of being left behind.

Lost to the sea forever.

I may have screamed. I couldn’t tell. It just sounded more like someone tried to drown Darth Vader and he just refused to die.

But all I remember was the panicked swim towards my pack. Which was soon followed by an even more panicked push up to the surface. Around it, the water doesn’t even look liquid anymore. It looks like it’s just a giant lump of a rock-mass.

Looming down. Waiting for me to prove my worth.

I’d imagine taking hundreds of steps down into the Red Rocks ampitheater, then going up on stage—is similar. If you’re one of the pros, maybe it’s not as scary.

The climb up

But fear doesn’t care about how awesome you are. All it cares about, is how far you’re willing to dive down (and swim back up)—to meet it.

And once you’re on stage, in the depths of everything you hated and loved most—then what?

What will you do about that fear?

In America, the answer to this is usually: Just face it. Do it. Power through.

But can you really power through just about anything?

For many people that I know nowadays, there’s the fear of being scrolled past. They’re talking about putting thembselves out there. And drowning in the sea of noise. The stakes might not physically be quite as high.

But the fear makes it feel like it.

Whatever it is, I prefer to turn to that ancient rock. Not that it’s alive or anything voodoo that I couldn’t understand. But more because I don’t think it’s about powering through anymore.

It just isn’t.

It’s about something else.

The check

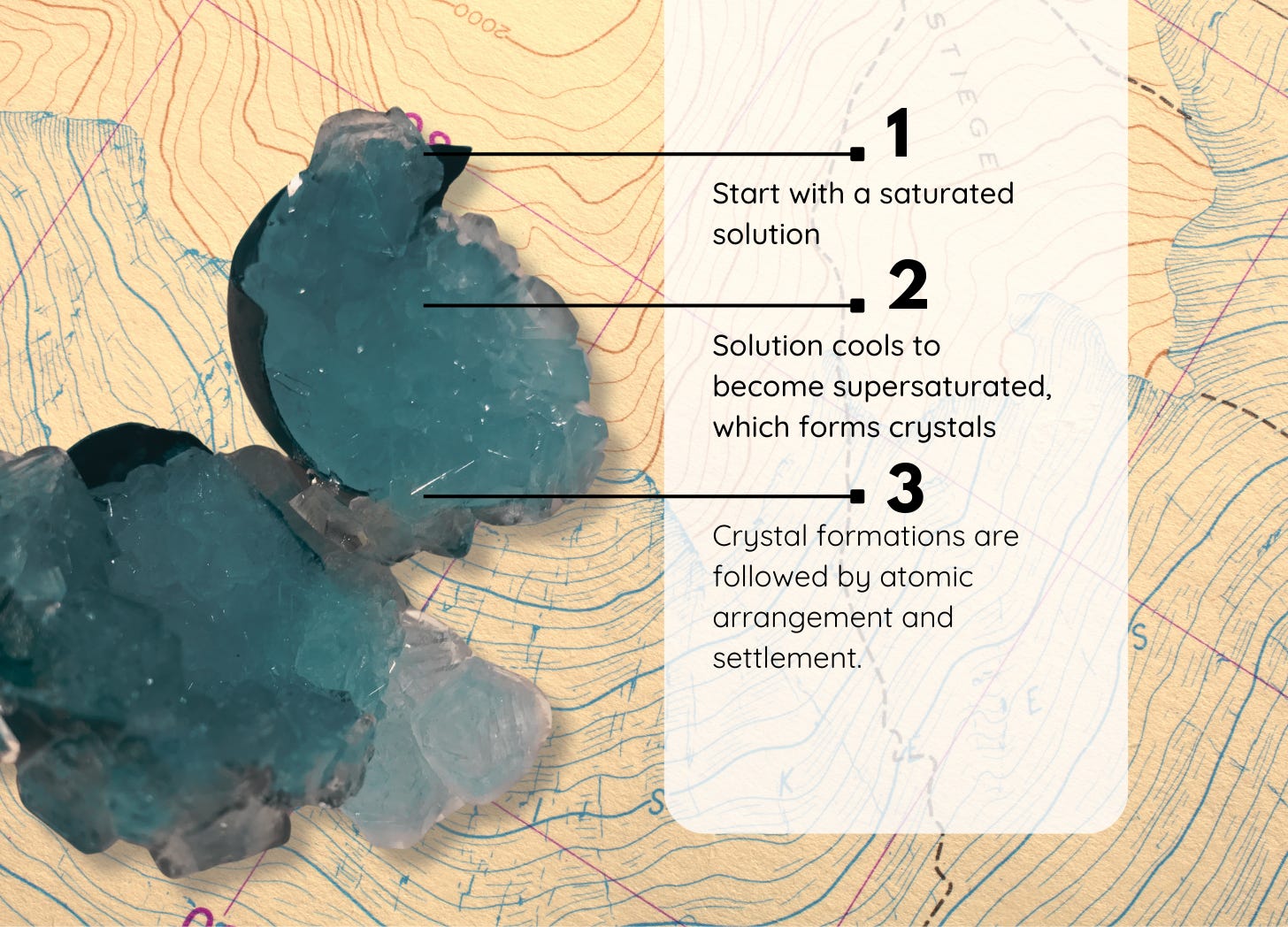

The weight of pressure, always splits things.

There’s almost a slow process of rearrangement. Of first the disorder and dying of the previous state: fear. From there: the ego is checked. And reordered. Until finally, we find a new state of being. Not so much a derivative. But a smaller variant. You can call it courage. But I don’t think that’s what that is. It’s more like … a crystallized version of the self. A settled nucleation.

And sometimes it takes being in these insane places for this to happen.

Because nothing cooks without some form of (re)arrangement. Whether it’s by pressure. Or heat. Or saturation. Or splitting. The alternative to this is staying raw. Which I guess is OK. For a while. Until we get tired of gnawing on ourselves.

This is probably why we like doing difficult things. Meaningless monotony is like that self-gnawing.

America likes to go big on everything. And maybe this is because big rocks like this exist in the land of the free. To the point where we just say,

You know what, we don’t know what to make of this rock. So we’re just going to try to match it. In size, audacity, and volume.

At the very least, art is born.

I want to remember this better the next time I get tired. The next time social media tempts us with the fear of being scrolled over. The next time I needed an ego-check when someone likes my work. The next time that feeling of the cold deep creeps up.

And definitely the next time I writhe like a baby seal in a diving suit. A suit that tells me …

I definitely ate one too many tacos!

-Thalia

PS:

If you want to go deeper on how places, settings, and architecture change our story—check out my other newsletter: Story Arks.

I created Story Arks because …

I believe that everyone deserves to choose how their story ends. Wherever they are.

Having restored 15,000+ square feet town halls and mapped food halls in the desert of New Mexico—”The Land of Enchantment”, I wanted to go deeper. About what exactly is it—that makes certain places—better for our work, writing, art, creation, health, and meaning.

Story Arks is where I talk about places. To find out how it changes how our story ends. It’s about real life and fictional stories. The curious and the fantastical. The weird and the wizardly. The classical and the comfortable.

You can read more about it here.

Here’s what one of our lovely readers, Margaret Taylor Kane, shared about Story Arks.

Thanks for the kind words, Margaret!

Specifically, here are some topics I’ll cover:

Unseen compartments that caused Titanic’s untimely demise.

The cars in Hogwarts Express: Train ride to timeless stories.

From restrooms to stadiums: Finding oneself in the crowd.

Noah’s Ark: The decks that saved humanity.

Top Gun’s jets that made the man, the myth, and the Machine.

Rocky Mountains of Colorado: deaths, victories, and discoveries.

What if Millenium Falcon’s piping is *not* on the outside

Does Elizabeth Bennet love Darcy or does she just love his big house?

In the spirit of Valentine’s week (which has really crept up on me this year!), I talked about Jane Austen’s Pride and Prejudice.

To subscribe to Story Arks, go here.

Can’t wait to see you there and geek out on some of these topics together!

-Thalia

This is very fitting because I’m staying home at the moment—I fell off a cliff, so to speak, a few days ago, and now I just have to take it easy, a message from my crystallized physiology and brain. This is my body’s usual way of dealing with things, stress, or illness, for the past 15+ years. No one has ever been able to explain to me why in any kinds of definitive rational terms, it’s just been a process of learning and NOT powering through, which I usually have been in the days preceding these forced rest events. Time to give up our ideas of ourselves. But I’ll do yoga anyways, to the best of my ability.